As Futurist Aesthetic Grows, the User Experience Spoils.

A Critique of my Favorite Aesthetic in Architecture.

It’s no secret that there is a love of Futurism and Brutalism in architecture schools across the globe. I’m as guilty of this crime against humanity (as some of my friends and family might believe) as any architect alive. I have gotten into knock down drag out arguments about why Boston City Hall is great with people who live there. I have brainwashed my wife into loving Brutalism by showing her how incredible Brutalist buildings can be. Here’s the thing, I think they rarely offer powerful experiences.

I’ve only cried while experiencing architecture twice, and neither were buildings in my favorite style (Brutalism). One was the Igreja Sao Domingos, if you read my blog post about it, you might figure out why, and the other was San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane by Borromini.

Other experiences that top my list are Parc Guell by Gaudi

The Austrian Postal Savings Bank by Otto Wagner

and Palácio de Monserrate by James Thomas Knowles (yes I know this building rips off Indian, Moorish, and Italian architecture, it just works don’t ask me)

None of these buildings are case studies in my favorite style of architecture, in fact they are in styles that my favorite architectural styles, Modernism, Futurism, and Brutalism, aimed to critique. In the early days of Modernism, it was essentially a critique on form followed by a critique on ornamentalism. Let’s review an incredibly truncated origin story for Modernism (which led to Futurism and Brutalism).

Form Follows Function: The Return to Good Architecture.

“Form Follows Function” was coined in 1896 by Louis Sullivan, who I hesitate to group with other architects many label as “Modernists”. He thought that it might be a good idea to design buildings per their use and not picking a plan out of a book, which was common practice in the 17th century. This became a battle cry for future modernists like Corbusier and Loos. Sullivan still believed in ornamentalism, which I believe plays a large part in improved experience. It was a direct condemnation of laziness in architecture, but after being abused and misused for decades it became a cause of it.

Ornament and Crime: The Return of Laziness in Architecture.

Twelve years later (what a great twelve years for architecture, it was) after Louis Sullivan coined the term “Form Follows Function”, Adolf Loos (who believed his best design was his incredibly heinous and definitely not racist residence for Josephine Baker. It’s not, his best is the American Bar)

wrote “Ornament and Crime.” This was a condemnation of architects wasting time designing ornamentation. Industrialization was taking over everything including architectural products. He argued against “wasting time” on ornamentation. At one point he flaccidly compares ornamentation to tattoos on criminals. How anyone, let alone well educated designers, found this convincing is confounding. This was in direct contradiction to the “Fathers of Modernism” the Secession Movement (which is why I don’t consider Wagner to be Modernist) and Sullivan.

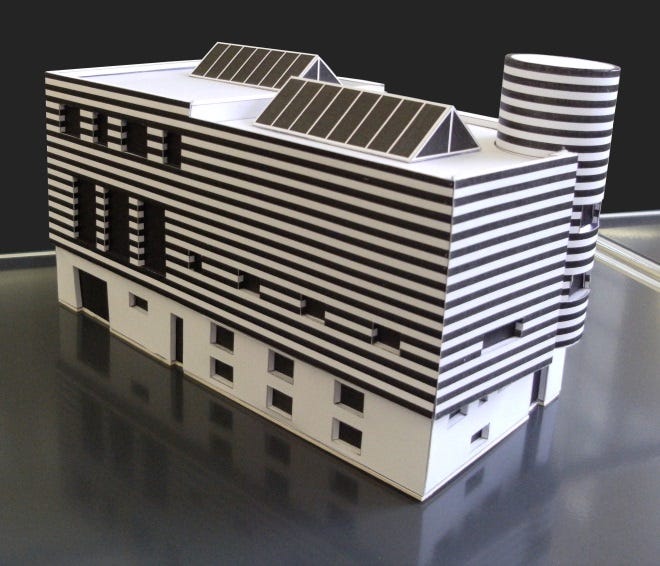

Corbusier is probably the most well known Modernist architect followed up Adolf Loos’ argument that ornamentation was an awful thing for architects to be involved in, and doubled down. One of his pillars of architecture is that architecture is a “machine for living”. What kind of machine values ornamentation and experience? This was a death blow to ornamentation in architecture, at least in European Modernism. It gave Birth to Futurism and Brutalism. (note: Superstudio was a well known firm that mocked these movements, so I want to be clear that not everyone followed Modernism mindlessly).

Frank Lloyd Wright had a huge influence on American architecture and his style of Modernism was distinct from, what is commonly referred to as the “International Style”, Modernism in Europe. Eventually it would come to America and bring Brutalism along for the trip across the pond.

Architecture: A Machine for Photographs.

Corbusier was notorious for extraneous efforts to stage his designs for photographs. “Now you’re on the trolley!” they would say (yes I did google 1920’s slang to get a good zinger here). People would go wild for a building that most architects, let alone layperson would never experience for themselves. I love architectural photography, especially when it is done well, but I have to admit that it played a huge role in what happened to architectural design in the future. We gave up on how a building can make you feel and designed for cool hip magazines. Either that or we gave up altogether and opted for an economical design.

For the most part Modernism and Brutalism died out, but the consequences of their ideals persisted. In the United States everyone is probably most familiar with the tragic demolition of Pennsylvania Station in NYC.

What was it replaced with? “The World’s Most Famous Arena”

This has been critiqued to death by Ada Louis Huxtable and every other architecture critic in existence. I’d recommend reading one of there summaries as they are much better writers than I. As a side note, the Moynihan Train Hall was recently opened as an homage to the lost Penn Station and has only taken roughly 30 or 40 years to get built. I recommend this review of it The Moynihan Train Hall’s Glorious Arrival.

The 2000s Experience.

I don’t think I need to tell anyone reading this how awful the 2000s has been for real life experience and social behavior. Social media has made visiting beautiful cities and places akin to waiting in line at the supermarket. Crowds of people holding up their phones for photographs without even enjoying the space has been one of the most cancerous experiences I can recollect. “The building is right there, you can literally experience it now!” I hear reverberating off of my skull as it begs to be shouted. In addition, internet journalism has hit critical mass as every famous architect tries to make the building that photographs the best, with the most click bait idea, so they can be in the most articles and blog posts (am I hypocritical? yes, yes I am). Here are a few super famous buildings from the last few decades, each of which I like, have visited, and have not been particularly noteworthy in person.

It’s not that I don’t like pictures of dystopian spiky buildings as much as the rest of the architectural profession, but I just don’t want to walk around in a dystopian spiky building. Could you imagine getting your first kiss in a dystopian spiky building? Could you imagine telling a funny joke standing outside one of these buildings? Of course not, these buildings don’t like jokes. They like brooding menacingly at the public.

There is a reason I’m glad Lebbeus Woods pretty much only made drawings; his buildings would be awful to experience. It’s not all bad, there are a handful of architects that design for experience and I think I’ll talk about them at some point, but as long as photography is king of architecture, I don’t see good experiences being key going forward. Preservation is going to be all the more important.