This will contain significant spoilers for Cyberpunk 2077 and its Phantom Liberty DLC!!

I also recommend listening to Tapes of Night City as it was the soundtrack for writing this.

Since I started playing Cyberpunk in late 2021 (well after its abysmal launch) I have been obsessed with the world built by Mike Pondsmith and brought to life by CD Projekt Red. I wrote to defend the architectural design from some well-written critical pieces that were tinted by the distaste for the soggy bottom that was the Cyberpunk launch. In hindsight, it feels silly to “defend” a game as well loved as Cyberpunk, but at the time the perspective of public opinion only STARTED to shift.

Cyberpunk 2077 Critique Revisited

Last time I wrote about Cyberpunk I was directly responding to critique and not really diving too deeply into the architecture of Night City. To recap the criticism was:

“

For a Cyberpunk game it loses the political message.

The expression of utilities doesn’t make any sense.

The rooms are oversized and out of scale.

“

I still think the first point is moot considering the ideas that the story explores and the second and third points are pretty nitpicky.

Over a few playthroughs I had a few ideas around how architecture is treated in game design in general as well as a lot of new ideas that cropped up around Dogtown newly created in the Phantom Liberty DLC.

Asset Reuse Theory

One of the most important successes of Cyberpunk is that the reuse of assets in Night City. The reason it is so important is that reuse of assets plays into the lore of a world ruled by corporations. Corporations will often reuse design and branding standards between locations and products. Typically, when assets are reused it becomes a balancing act between optimizing labor and preventing broken immersion by overused assets. The reason Night City can reuse as many assets as it does is, if I see the same sign, ad, or building in multiple locations, it fits into that idea of brand standards. In addition, an enormous amount of the city is still handcrafted around those reused assets.

A game like Forza Horizon 4 reuses assets to fill in city and towns so they don’t feel empty, but also so they don’t take an 84 years to model every cranny. It works in FH4 because the assets are experienced at high speed. It relies on the player not taking time to stop and investigate each building and interior. It fails when players break out of the typical gameplay systems.

Similarly NieR:Automata reuses many assets to fill out the ruined cities. Unlike FH4, it works because it functions as a driving force AND a way to reveal unique and important structures and vistas. Nier breaks down the most easily of the three games because it doesn’t require breaking the gameplay systems to break immersion. However, the pay off is worth it (i.e. seeing the amusement park or the castle for the first time).

Urban Design Theory

Everyone knows architects are experts in adjacent fields like Urban Design, just ask any urban designer I’ve ever worked with. Joking aside I think the way CDPR has designed the urban fabric of Night City reveals a surprising European bias. This allowed Night City to be more walkable than any current American cities with the exception of some of the oldest east coast cities like NYC, Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. The reason this is so interesting is because the critical philosophy of Cyberpunk is that a Corpocratic future has little to no redeeming qualities, yet the walkability and human scale of urban fabrics in Cyberpunk 2077 is largely improved.

American urban design has historically been car-centric. A car-centric culture results in high ratios of surface level parking and parking garages to actual buildings. While parking exists in Night City, the number of spaces per building is almost non existent. On top of that there are very few street parking spaces. No cars that drive around Night City park their cars, whether it be in a parking garage, surface parking, or on-street parking. Also, the parking garages and surface level lots are barely populated by cars. NCART, Night City’s metro and bus systems, must be making some serious eddies.

Gameplay-wise the lack of parking isn’t a big deal since one can park anywhere they want with no consequences. You can park on a sidewalk, in the middle of a 8-lane highway, or at the bottom of Coronado Bay. This also results in a fabulous walking and driving experience (ignoring the horrible steering controls. Light poles in Night City never stood a chance). Facades of buildings are open, sidewalks are bustling, and vistas are clear, creating an atmosphere common in European cities. My guess is that CDPR being based in Poland has lead to that all important European bias. As much as I love living in Columbus, I can’t say it would make a good video game city.

Is the DLC well designed?

The majority of the added content since the last time I critiqued this game was added in the Phantom Liberty DLC by way of Dogtown. Dogtown is a part of Pacifica, the playground for the ultrawealthy that ran out of money and was abandoned, that has been walled off from the rest of Pacifica for both political and security reasons. This is important because Pacifica is already known as one of the most dangerous areas in all of Night City, so to have a more dangerous version of that walled off is saying something.

When entering Dogtown for the first time, the first building V enters is the massive unfinished perfectly cylindrical sports arena. Within is a well designed platforming adventure through the abandoned parking garage. Eventually it opens up to the black market of Dogtown a series of shanty shops flank the central concourse. I found this moment so much more impactful than the mirrored experience you would have recently had when entering Pacifica proper with my mortal enemy Placide (all my homies hate Placide). The original moment is… well its fine, but kneecapped by the fact that I wandered into the area prior to this reveal and there really isn’t anything special about it (except for the crazy helicopter blasting explosive rounds into a construction site presumably murdering dozens of Scavs).

After your initial exploration of the stadium concourse, the center of the stadium is available to explore. There isn’t a LOT to do here, but you get a pretty great view of one of the massive flying ships you see coming in and out of Night City. This was the first time that I realized that these are the Cyberpunk version of massive shipping container barges, as one is crashed in the center of the stadium and the crates are being harvested by the gang in charge of Dogtown. The containers become a central part of the architecture of Dogtown slums. After leaving the stadium for the area that is Dogtown proper, the area is surrounded by a canyon of half-built skyscrapers and high rises.

The rest of Dogtown is broken into two parts.

Dogtown Part 1. Shipping Container Architecture.

All of the buildings built after the Pacifica project was abandoned were constructed with left over shipping containers that, as mentioned above, have been illegally harvested. Shipping container architecture is not a legitimate design solution in our reality (it drives me crazy, such a bad trend), but Dogtown creates an environment where the biproduct of criminal activity (shipping containers) is an effective building material. This is such a deep cut architectural idea that I’m not even sure whether it was intentionally explored.

Dogtown Part 2. Learned From Learning from Las Vegas.

The other set of structures in Dogtown are a series of “Ducks” and “Decorated Sheds”. In Learning from Las Vegas, Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi and Steven Izenour analyze the non-City of Las Vegas and its programs (parking lots, casinos, churches, and hotels). It also analyzes the main types of structures that house these programs, the “Duck” and the “Decorated Shed”.

A “Duck” is a structure that doesn’t need a sign for you to know what it is. These often appear as a caricature of a symbol or object. An example would be this absolute banger. Some obvious examples from the Dogtown include the Heavy Hearts Club, a giant pyramid similar to the Luxor

and the greatest Bass Pro Shop on Earth

and Brainporium which is shaped like a giant head and sells brain dances.

A “Decorated Shed” is a structure that relies on signage to tell you what is inside. Obvious examples are big box stores and Holiday Inns. In Dogtown there are signs everywhere, including on the stadium we can in through. Examples of this in Dogtown include the church and The Grand Azalea.

The Symbolism at the Black Sapphire.

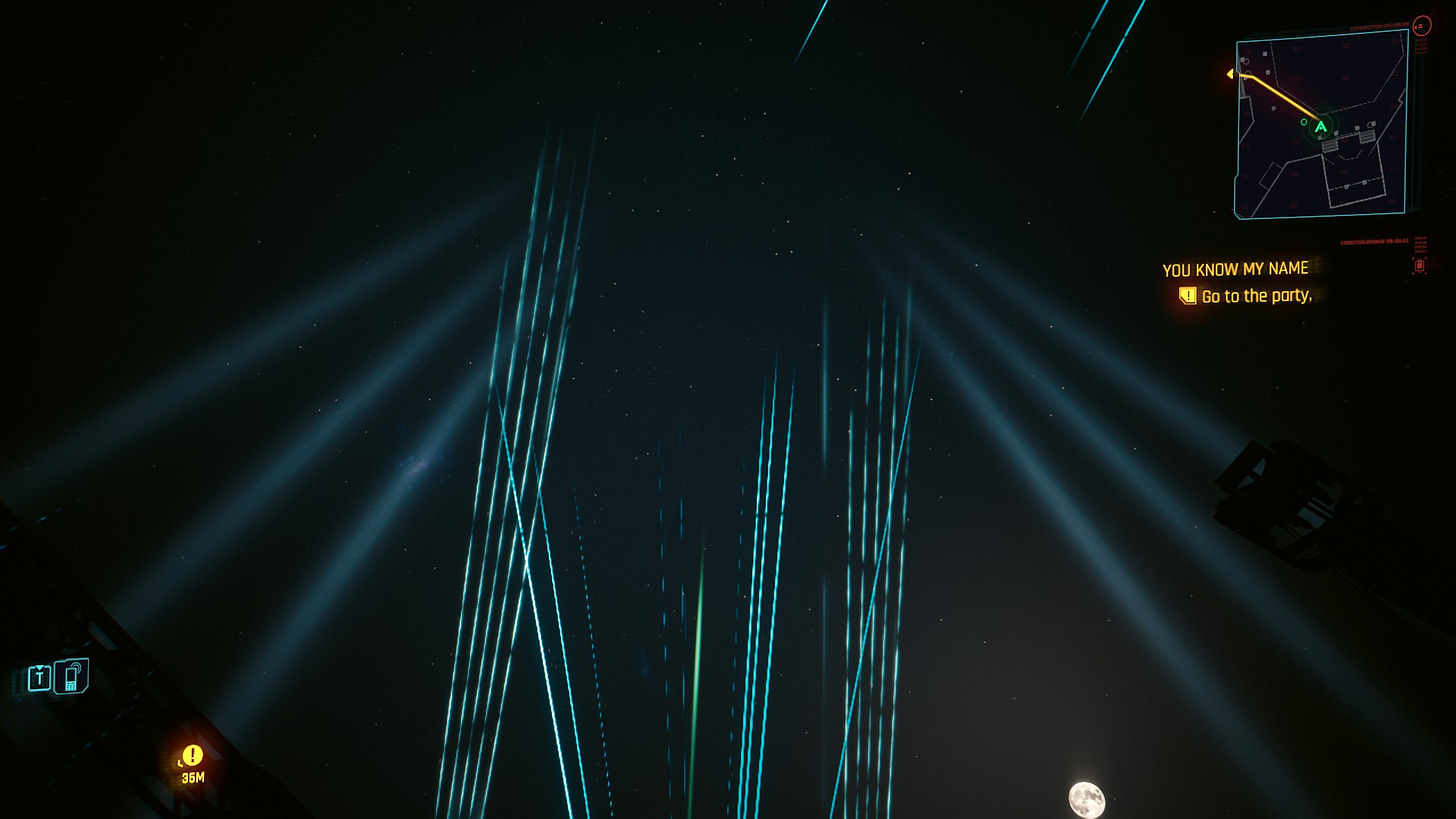

During the main storyline V enters the Black Sapphire, a massive skyscraper hotel that the Warlord that rules over Dogtown stays. There is a party where many politicians and the well connected of Night City come to Dogtown to watch a pretty incredibly rendered performance by Lizzy Wizzy (Grimes). During normal operating hours the Black Sapphire is coated in black and gold Art Deco motif, but during event they want show off power so they implemen hologram Neo Classical columns and fascist inspired detailing coat the Art Deco ornamentation to create an Albert Spear inspired fever dream (complete with a Cathedral of Light reference). The idea that the designers had the architectural understanding to allow a building to reflect political intent is incredibly nuanced and not something I would ever expect a game studio to understand. It is a really impressive reference.

I love that a handful of buildings was able to spark this many ideas and references. It’s such an incredible achievement that this game was able to end in the state it is in. I can’t wait for the sequel in the distant future.