House on Ile Rene-Levasseur

I’ve have had almost no time lately. I have had a number of real life events that have absorbed my free time, as a result my posts have become more and more sparse and less and less researched. I haven’t had time to play games, I haven’t had time to research historical architecture (I guess I could just throw together a bunch of random facts I remember from college, but that’s not going to be satisfying for anyone) and I definitely have not had time to visit real sites to photograph and record architectural details (I did get a chance to visit the new Crew stadium and a critique will be forthcoming, but I wasn’t allowed to take photographs, so this will have to wait until I can go to a game). I could write about realized projects without visiting the sites, but I don’t find much value in that. So… let’s review some theoretical architecture.

When I was a college student I had the opportunity to see Mark Foster Gage lecture. At the time, he was an up and coming architect from New York. He opened with the line “if you want people to talk about architecture, you have to get them drunk first. So a server will be coming around with shots”. As cringe as telling a joke about alcohol abuse to college kids (especially ones under as much stress as architecture students were) is, I still loved that it showed a willingness to not take the profession so seriously. He mostly talked about the “Penthouse in Manhattan” and a couple of other realized projects. It wasn’t until years later that I found out he has an incredible portfolio of theoretical projects. My school was known for pragmatism in architecture, so he might have toned back his presentation as not to offend the duller side of the profession.

Either way, I want to talk about a few of his projects and the first one is House on Ile Rene-Levasseur.

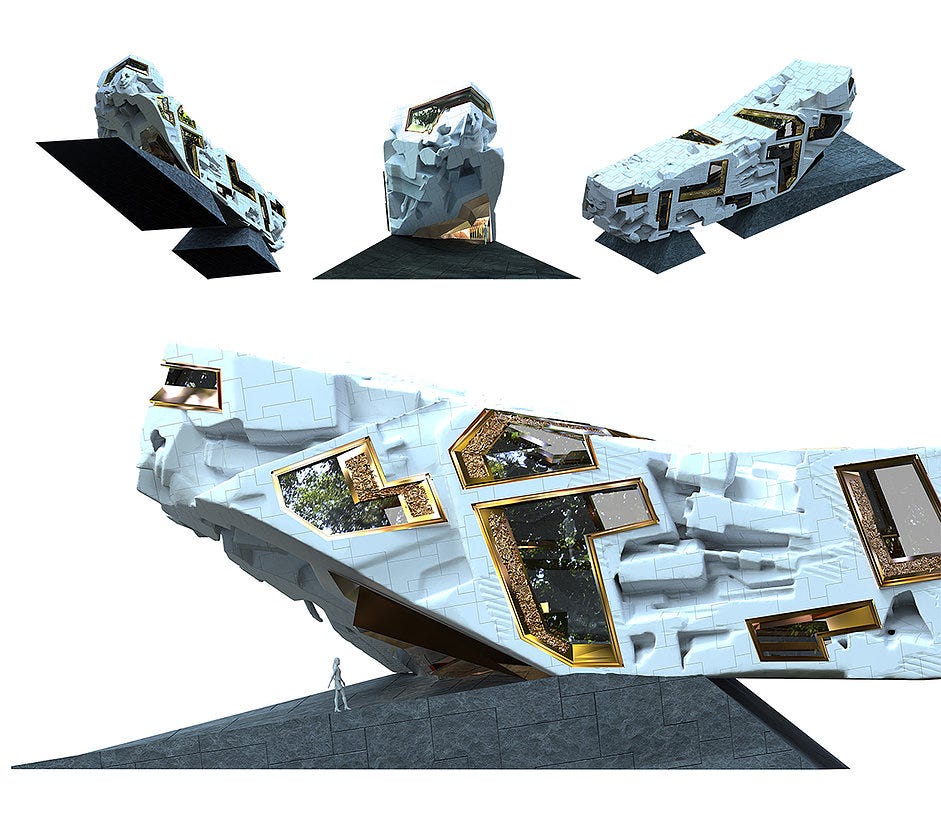

House on Ile Rene-Levasseur is a vacation home in a Taiga old growth forest in Canada. It serves as a commentary on the pristine vacation homes of modernism. Gage designs a home with the direct purpose of aging into the environment. He directly contrasts it to the Farnsworth and Glass House from Mies and Johnson respectively.

For a long time these (and Falling Water) have been the “ideal” way to collaborate with nature. I share Gage’s thought that these not only juxtapose with their natural surroundings, but the pristine quality is impossibly difficult to maintain. Gage develops a project with the intent of low maintenance especially when the occupants are not there (most of the time for vacation homes).

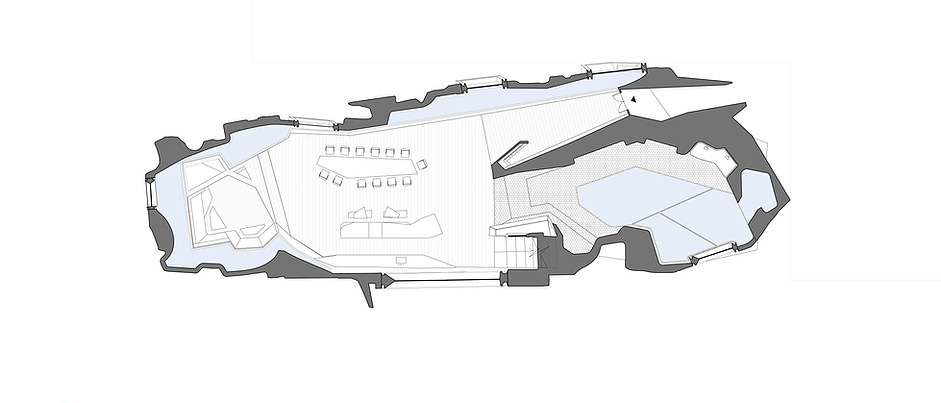

The house combines the straight walls of modernism and traditional human built habitats with natural rock formations and plant growths of an old growth forest. It mimics the way light travels through a canopy into the single connected space.

House on Ile Rene-Levasseur is a powerful way to address a host of problems caused by humans trying to live in places that are not easily inhabitable by us. Build something beautiful with nature and let nature absorb the structure into its landscape.

This design (and many of Gage’s unbuilt work) is informative on how humans should look at problems when they contradict the Anthropocene. It is not only a critique of the aesthetic of modernism, but it is a critique of its humancentric ego.